When I first started training in Uri’s unique Alexander Technique studio in Tel Aviv I had absolutely no aspirations to teach. My dreams at the time were to be a renowned documentary filmmaker. It felt confusing to me that I had somehow ended up in a quiet, modest and unheard of corner in Tel Aviv, working with my hands and breath to rebalance myself and others. Being in this place made no sense to me because it didn’t at all fit with my well-thought out and goal-oriented career plan. But it really felt right. I had found a teacher that was helping me understand my humanity and a way to live in the most simple and easeful way.

‘Look after the means whereby and the ends will come of themselves and by themselves.’

Over the last decade I have refused, wrestled with and eventually come to accept this quote by F.M Alexander, the man who created the technique. My understanding of it is that instead of obsessing over single-minded goals I can choose a preferred direction and set up the best possible conditions for myself to go that way. The Alexander Technique teaches a student to stop (or inhibit) before they take action. This allows for a simple pause, a breath and a softening. It opens up possibilities that might go unnoticed when we focus solely on the goal ahead. Stopping before moving, doing or speaking allows us to slow down enough to be here, aware of our aliveness within this moment.

The ability to focus on healthy conditions rather than successful outcomes helped me understand my creative process and distill some key lessons I had learnt as a film student.

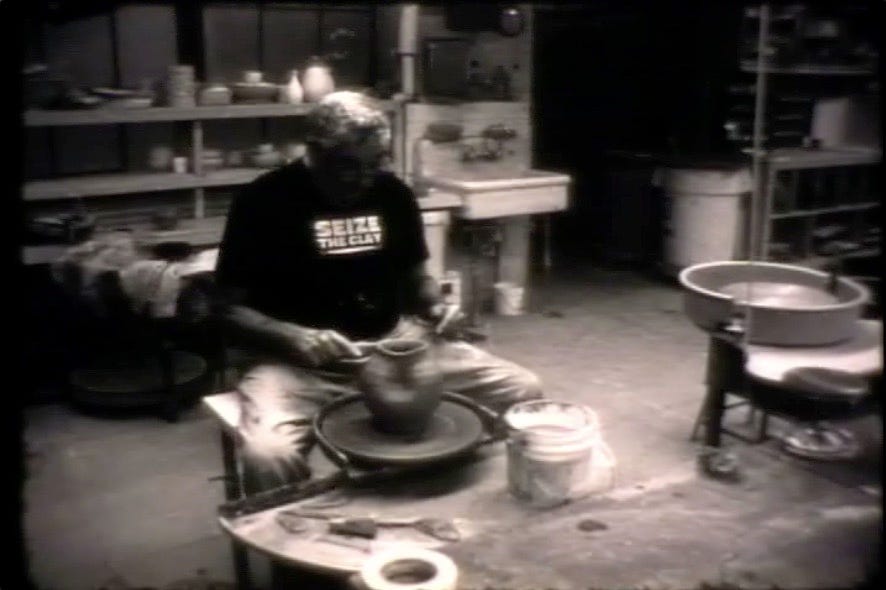

After completing an academic art history degree, my year at film school was a terrifying and transformative time. In the first week I was instructed by my teacher Andrea, to borrow a 16mm camera from the equipment room and ‘go make your first film’. The exercise was simple: to make a 3 minute film with a beginning, middle and end. I made a very short film that captured the creation of a ceramic pot. This initial experience taught me an enormous amount. The following three skills are ones that I continue to foster in myself and my students as I believe that they are essential for our creativity and our health:

Trust. Contacting a ceramic studio out of the blue and asking them if I could randomly film one of their potters felt daunting. I was amazed that they were so willing to help a student filmmaker and that Les, the old man in the film, was so happy to spend a Saturday filming with me. I know it seems childishly simple but this experience taught me that the world is full of kind strangers who are willing to help me when I ask.

There have been subsequent moments that have felt much more challenging than this and help has felt almost impossible. For me, the only way through these tough experiences has been to remember that I can trust my intuition and have faith that I exist in a cooperating universe. Asking for help, even as a silent prayer, has amazingly always brought the necessary guidance, encounter or direction.

Yield. Before the shoot at the pottery studio I envisaged every single second of the film. My imagined plan and shot-list gave me a sense of security and control when I showed up with my camera to film. But the actual experience that day was completely unexpected and far better than anything I had imagined. Letting go of my rigid structure and instead responding in real time to Les, as he threw, pinched and patted a lump of clay allowed me to capture images that felt authentic and surprising. This is not to say that my planning was a waste of time: in fact I believe that it enabled the success of the shoot that day. But instead of being locked in by the minutiae of every little detail it provided a loose framework that allowed Les to do his thing and me to capture and respond to it. I have observed that this ability to yield and let go of a plan is essential for healing. It allows for real relaxation, which in turn provides an overstressed nervous system the opportunity to release and reset. I have come to believe that a healthy nervous system is absolutely critical for wellbeing.

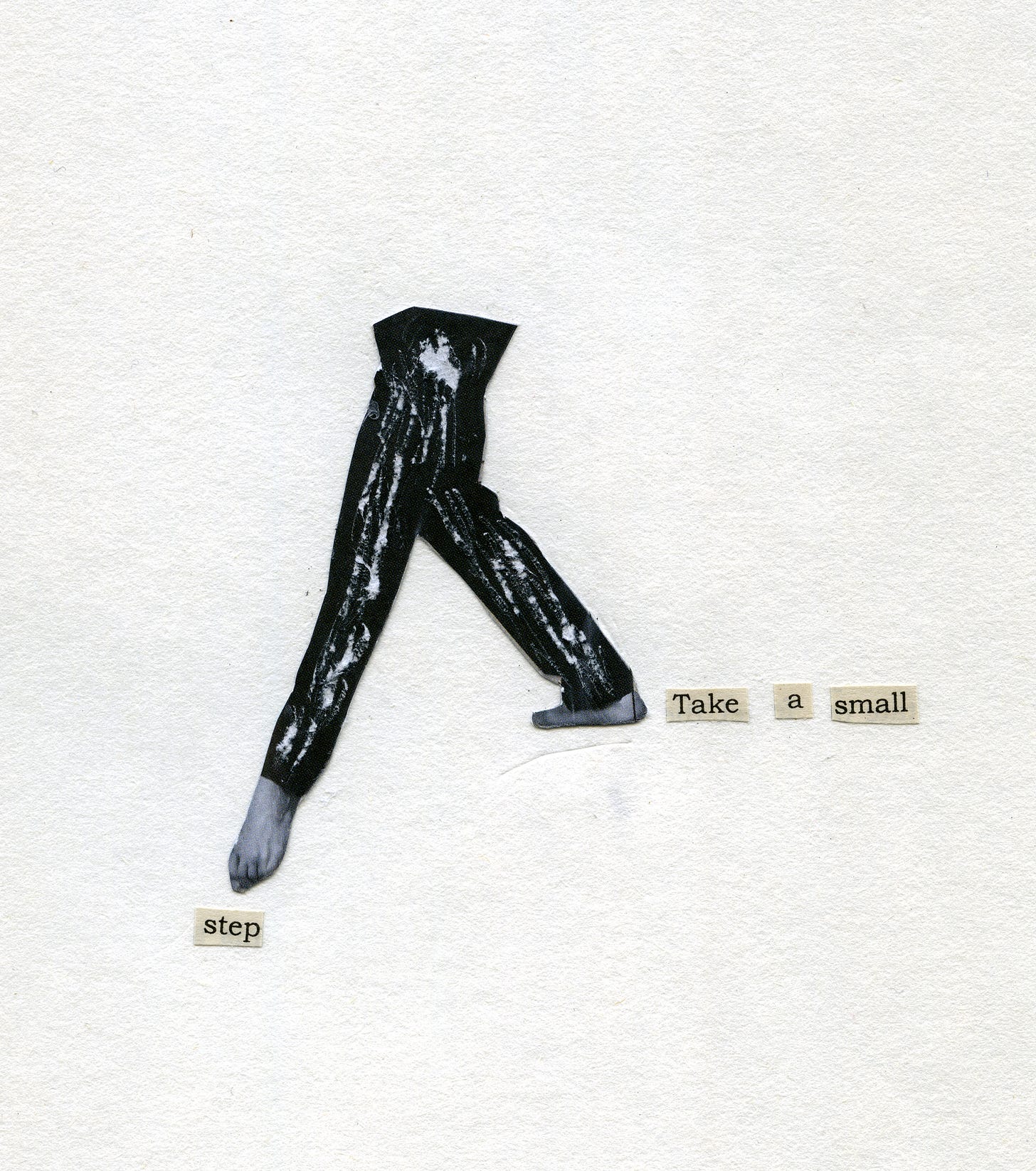

Being Seen: After completing my first cut of this little film I was TERRIFIED to show it to my class. As I connected my hard drive to the big screen I apologised about a thousand times for my ‘terrible’ film. But as the images flickered in front of the other students I had an opportunity to see it with fresh eyes. They experienced it in a way that I couldn’t. I observed their reactions and realised that being seen isn’t about being good or bad or about being accepted or rejected. It’s about having the chutzpah to be comfortable with being imperfect and realising that growth can only happen when we are brave enough to share with others. As a student at school and university I had conditioned myself to believe that the grades I received for my work defined and determined my worth. Learning how to make films was an initial step in an education that broke this conditioning. Getting an A* or a D was irrelevant. What counted was much more energetic. A film felt successful if it made the viewer feel something. Enabling a person to laugh, cry, question or connect through seeing a sequence of moving images felt powerful, real and relevant.

Working in Uri’s studio allowed me to discover dormant parts of myself. Instead of caring about fitting into a neat box with a clearly defined label I started to love my multi-faceted nature. With time I started to slowly share these different parts of myself with the world. It felt scary at first: I remember feeling self-conscious when I first shared my artwork online (who was I to call myself an artist?!), and I remember feeling terrified before I taught my first yoga class (who was I to call myself a yoga teacher - I can barely touch my toes!) But every time the experience of being witnessed has been essential part of my growth and my healing.